| Articles | ||||||||||||||||

|

Thoughts on Long−Term Energy Supplies: Scientists and the Silent Lie The world's population continues to grow. Shouldn't physicists care? The most sacred icon in the "religion" of the US economic scene is steady growth of the gross national product, enterprises, sales, and profits. Many people believe that such economic growth requires steady population growth. Although physicists address the problems that result from a ballooning population—such as energy shortages, congestion, pollution, and dwindling resources—their solutions are starkly deficient. Often, they fail to recognize that the solutions must involve stopping population growth. Physicists understand the arithmetic of steady, exponential growth.1 Yet they ignore its consequences, including the first law of sustainability: "Population growth or growth in the rate of consumption of resources cannot be [indefinitely] sustained."2 (See Ben Zuckerman's letter to the editor, Physics Today, July 1992, page 14.) Sustainability requires solutions that will be effective over time periods much longer than a human lifespan. Indeed, Paul Weisz makes a case on page 47 of this issue that many time−honored 20th−century energy sources, such as petroleum, natural gas, and coal, have been reduced to the point that their longevities are now expected to be of the order of a human lifespan.

Physicists and energy

Among physicists, there is a growing recognition that we have a responsibility to become more directly involved in the scientific aspects of problems facing society. As an example, consider the April 2002 special issue of Physics Today, which addressed specific energy problems. Let's focus on two of the articles in that issue: Stephen Benka's introductory essay, "The Energy Challenge" (page 38), and Ernest J. Moniz and Melanie A. Kenderdine's lead article, "Meeting Energy Challenges: Technology and Policy" (page 40). The titles alone convey a common commitment to society. In his essay, Benka outlined the magnitude of the challenge by citing projections from the US Department of Energy: Between 1999 and 2020, the world's total annual energy consumption will rise 59% and the annual carbon dioxide emissions will rise by 60%, while the world population increases from 6.0 to 7.5 billion people. But here's the rub: Scientists may call for solutions to meet the rising demands of population growth, but as long as we postulate the continuation of that growth, the attendant problems of energy consumption and increasing CO2 emissions cannot have long−range solutions. The two articles in Physics Today fail to identify stopping growth as a necessary condition for the success of any proposed long−range solutions to the problems caused by population growth. Scientists have occasionally acknowledged that population growth is the major cause of our problems. But I wonder whether their general reticence stems from the fact that it is politically incorrect or unpopular to argue for stabilization of population—at least in the US. Or perhaps scientists are simply uncomfortable stepping outside their specialized areas of expertise. Unchecked population growth as a source of problems is not news. More than 200 years ago, mathematician Robert Malthus (17661834) addressed the issue in his famous essay.3 He understood that populations had the biological potential for steady growth and that food production did not. Today, energy production does not have the capability of steady growth. Nevertheless, we are all aware of nonscientists with academic credentials who proclaim that our modern technology has proven Malthus wrong. The most egregious of the high priests of endless growth was the late Julian Simon, professor of economics and business administration at the University of Illinois and later at the University of Maryland. In 1995, he wrote: Technology exists now to produce in virtually inexhaustible quantities just about all the products made by nature. . . . We have in our hands now . . . the technology to feed, clothe and supply energy to an ever−growing population for the next seven billion years.4 In the eyes of the general public, the silence of scientists on the problems of population growth seems to validate the messages of the politically appealing and influential Julian Simons of the world.

Supply shortages

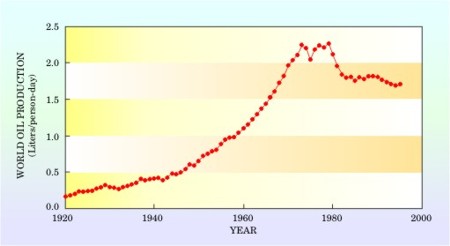

In addressing the problems, Benka noted that "most of the growth in all three areas [energy consumption, CO2, and population] will take place in rapidly developing parts of the world." It is expedient to blame others, but because the US consumes so large a fraction of the world's energy resources, we Americans are effectively the worst offenders in those areas. Our population growth rate of more than 1% per year is the highest of any industrial nation. The US can't preach that other countries should limit their population growth unless we are willing to set an example and do so first. Benka later argued, "It seems certain that the world will continue to rely heavily on hydrocarbon combustion for the foreseeable future. . . . However we must develop alternative energy sources." To be fair, Benka was not sanguine about the problem of energy shortages. His essay is partly a call to arms. But the evidence (see Weisz's article) indicates that some fossil−fuel resources may be in trouble within the next few decades. When physicists suggest that the US has resources and technological potential to meet the needs of an ever−growing economy, it's like inviting the public to dinner without having checked to see if there is sufficient food in the cupboard. Most educated people understand that populations can't grow forever. But forever isn't really the issue. Already, population increases and consumer demand are taking big bites out of our energy resources. Of natural gas, Moniz and Kenderdine wrote that "US consumption represents roughly half of that for the industrialized world. . . . Developing Asia, Central America, and South America . . . are each expected to triple their demand over the next twenty years." A geological study published in 2003 reports that per capita annual production of natural gas is decreasing in Canada, Mexico, and the US.5 Production of natural gas in North America may be near the start of its terminal decline. Of petroleum, Moniz and Kenderdine reported that world oil consumption is expected to grow by 60% in the first two decades of the 21st century and that China expects a five−fold increase in vehicles by 2020. Some optimistic researchers include in their tabulation of world reserves the oil shales of western Colorado (about 500 billion barrels); the Athabasca Oil Sands of Alberta, Canada (about 300 billion barrels, potentially); and the heavy oil under Venezuela (about 2 trillion barrels).6 Those quantities are huge compared to the US annual consumption of approximately 6 billion barrels, but the important question to ask is, What is the net energy gained after investing the energy it would take to recover those very hard−to−extract resources? Physicists must include the net energy in any recommendations that we make to use those fuels in the future. Moniz and Kenderdine also wrote about "products derived from gas−to−liquid conversion [meaning natural gas], gasification of coal, and biomass." But if natural gas in North America is near the start of its terminal decline, there won't be much left to convert into other potential uses. They argued that CO2 emissions can be reduced by switching to "less carbon−intensive fossil fuels—for example, natural gas instead of coal for electricity generation—[this is an] economical way to reduce carbon intensity and meet growing demand." But the switch from coal to natural gas to generate electricity in the US was made a decade or so ago and the predictable effects are now evident: declining production, imminent shortages, and the rapid price increases of natural gas. Researchers continue to debate when the peak of world petroleum production will be reached. Analytical estimates range from 20047,8 to about 2025.9 But from a per capita perspective, world petroleum production reached a peak in the 1970s (see the figure). I believe future historians may identify this peak as one of the most important events in all of human history.

The silent lie

In the Physics Today essay and article, population growth is given as a cause of the problems identified, but eliminating the cause is not mentioned as a solution. We are prescribing aspirin for cancer. Indeed, the solutions outlined in the articles would only make the problems worse. To appreciate what I mean, consider the "theorems" of economist Kenneth Boulding.10

The Dismal Theorem: If the only ultimate check on the growth of populations is misery, then the population will grow until it is miserable enough to stop its growth. The Utterly Dismal Theorem: Any technical improvement can only relieve misery for a while, for so long as misery is the only check on population, the [technical] improvement will enable the population to grow, and will soon enable more people to live in misery than before. The final result of [technical] improvements, therefore, is to increase the equilibrium population, which is to increase the sum total of human misery. The Moderately Cheerful Form of the Dismal Theorem: If something else, other than misery and starvation, can be found which will keep a prosperous population in check, the population does not have to grow until it is miserable or starves; it can be stably prosperous. In 1970, the CBS broadcaster Eric Sevareid rephrased the theorems even more bluntly: "The chief source of problems is solutions."11 Physicists develop solutions to problems, but when the underlying cause of those problems remains neglected, we are effectively perpetuating a lie—what Mark Twain has called the silent lie: Almost all lies are acts, and speech has no part in them. . . . I am speaking of the lie of silent assertion; we can tell it without saying a word. . . . For instance: It would not be possible for a humane and intelligent person to invent a rational excuse for slavery; yet you will remember that in the early days of emancipation agitation in the North, the agitators got but small help or countenance from any one. Argue and plead and pray as they might, they could not break the universal stillness that reigned, from pulpit and press all the way down to the bottom of society—the clammy stillness created and maintained by the lie of silent assertion—the silent assertion that there wasn't anything going on in which humane and intelligent people were interested. The universal conspiracy of the silent−assertion lie is hard at work always and everywhere, and always in the interest of a stupidity or a sham, never in the interest of a thing fine or respectable. It is the most timid and shabby of all lies . . . the silent assertion that nothing is going on which fair and intelligent men [and women] are aware of and are engaged by their duty to try to stop.12

What do we do?

Here is a list with which to start:

The physics community cannot launch a major campaign aimed at stabilizing the US population. That's not physics. But when physicists assume authoritative roles to solve the societal problems caused by population growth, professional responsibility requires that we stress the importance of stopping population growth as a central part of all solutions. We are not telling lies of silent assertion in the interest of the tyrannies and shams that Twain cites. Rather, we are tiptoeing around the issue in the name of political correctness. We can't be proud of that. As Mark Twain wrote, "[It] is the most timid and shabby of all lies."12

1. A. A.

Bartlett, Am. J. Phys. 46, 876 (1978).

2. A. A. Bartlett, Population and Environment 16, 5 (1994).

Reprinted in Renewable Resour. J. 15, 6 (Winter 199798).

3. See T. R. Malthus, in An Essay on the Principle of Population: Text,

Sources and Background, Criticism" P. Appleman, ed., W. W. Norton,

New York (1976).

4. J. M. Simon, The State of

Humanity: Steadily Improving, CATO Policy Rep. vol. 17, no. 5, Cato

Institute, Washington, DC (Sept.Oct. 1995), p. 131. For a critique,

see A. A. Bartlett, Phys. Teach. 34, 342 (1996).

5. W. Youngquist, R. C. Duncan, Nat. Resour. Res. 12, 229

(2003).

6. W. L. Youngquist, GeoDestinies: The

Inevitable Control of Earth Resources Over Nations and Individuals,

National Book, Portland, OR (1997), p. 215.

7.

A. A. Bartlett, Math. Geol. 32, 1 (2000).

8. K. S. Deffeyes, Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage,

Princeton U. Press, Princeton, NJ (2001).

9. J.

D. Edwards, Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 81, 1292 (1997).

10. K. Boulding, in Collected Papers [by] Kenneth E. Boulding,

Vol. 2, Colorado Associated U. Press, Boulder, CO (1971), p. 137.

11. E. Sevareid, CBS News, 29 December 1970, quoted in T. L. Martin, Malice

in Blunderland, McGraw−Hill, New York (1973), p. 23.

12. M. Twain, The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg and Other Short Works,

Prometheus Books, Amherst, NY (2002), p. 159.

Figure 1. World daily production of petroleum per capita has been steadily dropping since the 1970s, when it was roughly 2 liters per person−day. Currently, US consumption is about 4 liters per person−day. As petroleum production struggles to keep up with growing demand, and as world population continues to grow, it is unlikely that world per capita production can ever again rise to the levels reached in the 1970s. (Adapted from ref. 7.)

© 2004 American Institute of Physics

|

Sponsored links

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||